How Stanford professor BJ Fogg’s revolutionary behavior model can transform your habits through the strategic use of triggers, motivation, and ability

Dr. BJ Fogg, founder of the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford University, has revolutionized our understanding of behavior change

Last week I attended a Communications Media Managers Association (CMMA) event in Plano, Texas, where I had the opportunity to hear Stanford University professor BJ Fogg speak about “Hot Triggers & Rituals: The New World of Persuasion.” Despite some technical difficulties that delayed his presentation and forced him to condense his material, the insights he shared were immediately practical and profound.

What makes Fogg’s approach to behavior change so compelling is its remarkable simplicity combined with its explanatory power. Instead of relying on willpower or motivation alone, Fogg has identified a precise formula for how behaviors occur and how they can be intentionally designed or changed.

In this post, I’ll share what I learned about Fogg’s behavior model and how you can apply these concepts to create positive changes in your own life—or to design products and experiences that effectively influence behavior in others. The applications range from personal habit formation to product design, marketing strategies, and organizational change initiatives.

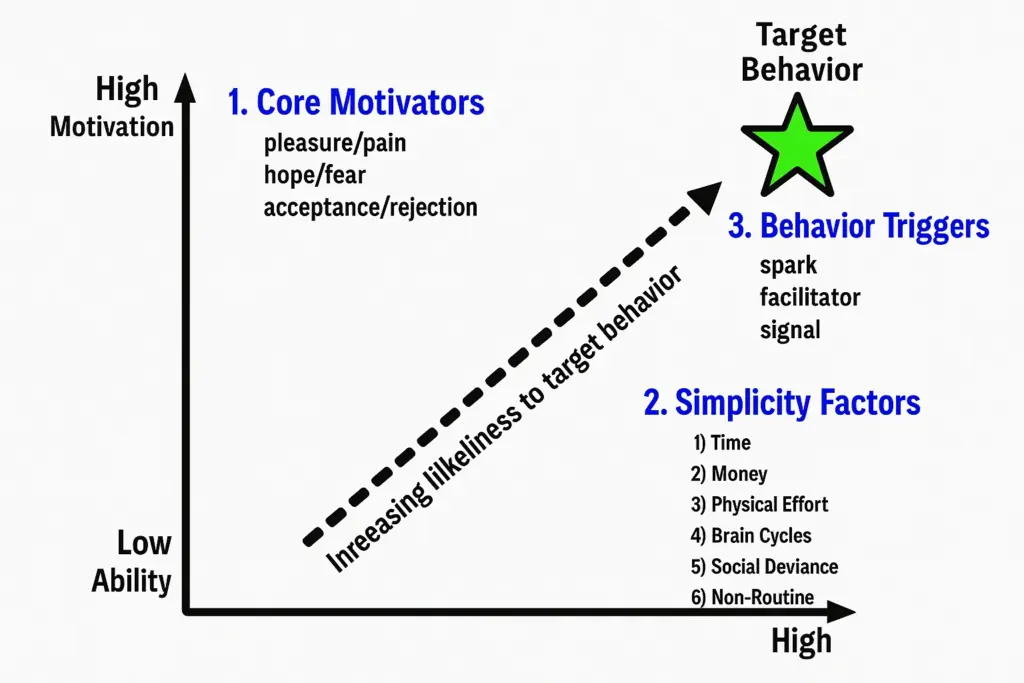

The Fogg Behavior Model: B=MAP

At the core of Fogg’s work is a deceptively simple equation: B=MAP. This formula states that a behavior (B) occurs when motivation (M), ability (A), and a prompt (P) come together at the same moment. If any component is missing, the behavior won’t happen.

Let’s break down each component:

- Motivation: Your desire to perform the behavior

- Ability: Your capability to perform the behavior (how easy it is)

- Prompt: The trigger or cue that reminds you to perform the behavior

What makes this model so powerful is that it explains both why behaviors happen and why they don’t. If you want to engage in a behavior but aren’t doing it, one of these three elements must be missing or insufficient.

The genius of Fogg’s model is that it reveals why willpower often fails: trying to increase motivation is actually the hardest way to change behavior. Making the behavior easier (increasing ability) or creating better prompts are typically more effective approaches.

The Three Core Motivators

According to Fogg, human motivation is driven by three core motivator pairs, each working on a pleasure-pain spectrum:

- Pleasure/Pain: Our most primitive motivator, operating immediately and powerfully

- Hope/Fear: Our anticipation of future outcomes, both positive and negative

- Social Acceptance/Rejection: Our desire to be socially accepted and fear of being rejected

These motivators explain why we’re drawn to certain behaviors and repelled by others. Each person’s relationship with these motivators varies based on their personality, experiences, and current circumstances.

However, Fogg emphasizes that increasing motivation is often the wrong approach to behavior change. Motivation fluctuates naturally and can be difficult to maintain long-term. Instead, he suggests focusing on the other two components: ability and prompts.

When designing for behavior change, it’s more effective to make the behavior easier than to try to increase someone’s motivation. This insight challenges conventional wisdom about habit formation and willpower.

The Six Simplicity Factors

Fogg identifies six factors that influence how “simple” (or easy) a behavior seems. The more of these factors at play, the more difficult the behavior becomes:

- Time: How long it takes to complete

- Money: The financial cost involved

- Physical Effort: The physical exertion required

- Brain Cycles: The mental effort and focus needed

- Social Deviance: How much it goes against social norms

- Non-Routine: How different it is from your established habits

Fogg explains that simplicity is subjective and contextual. What’s simple for one person may be difficult for another, and what’s simple in one situation may be difficult in another.

An important insight is that simplicity is determined by your scarcest resource at any given moment. If you’re short on time, even quick tasks can feel difficult. If you’re mentally exhausted, even simple decisions become challenging.

Fogg argues that you can increase a person’s ability to perform a behavior not by training them, but by making the behavior simpler. This is why “tiny habits”—behaviors that require minimal time, effort, and resources—are so effective.

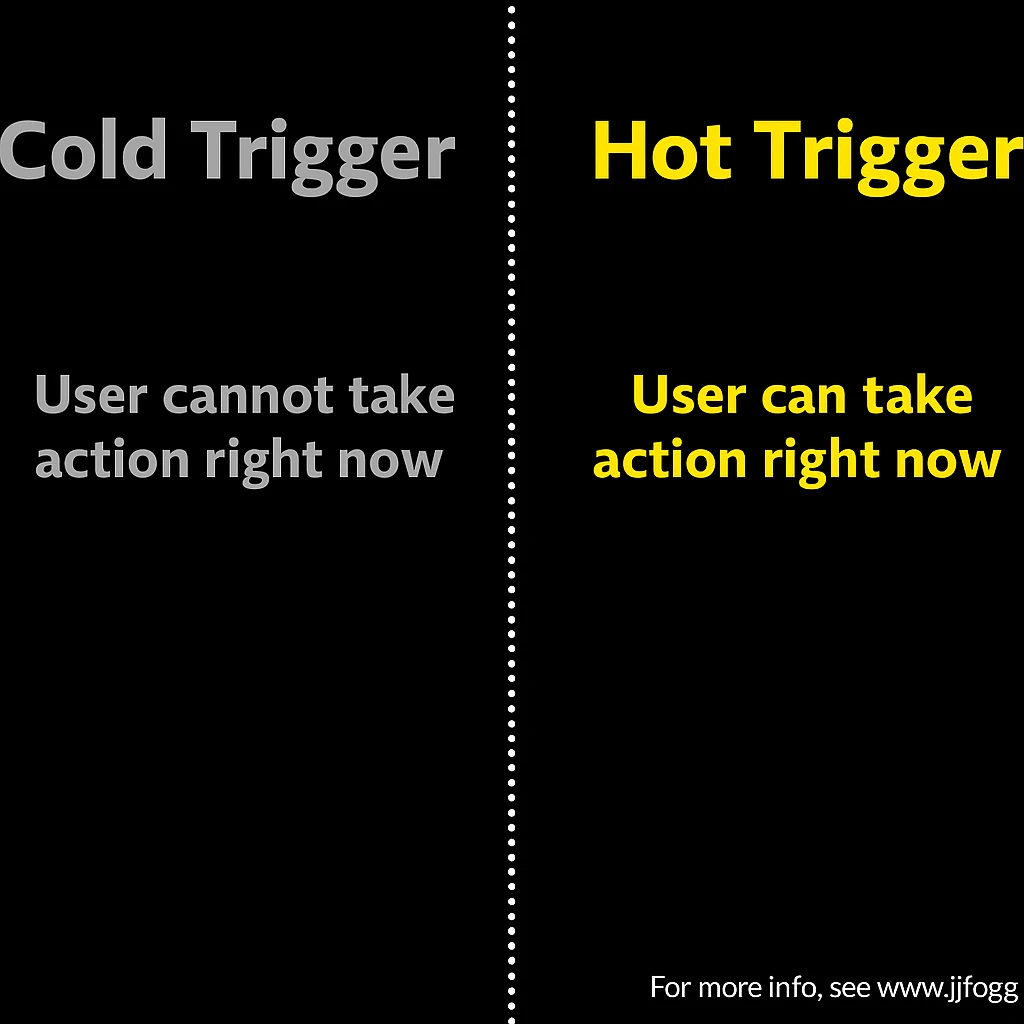

Hot vs. Cold Triggers

Perhaps the most applicable concept Fogg shared was the distinction between hot and cold triggers:

- Hot Triggers: Prompts that allow for immediate action

- Cold Triggers: Prompts where immediate action isn’t possible

Hot triggers are significantly more effective because they allow for immediate action when motivation and ability are present. A Facebook notification that lets you click immediately is a hot trigger. A billboard advertising a website you can’t visit while driving is a cold trigger.

Fogg’s advice is simple but powerful: “Put hot triggers in the path of motivated people.” In other words, make sure your prompts appear when people are both motivated and able to act.

The most effective behavior design doesn’t just create prompts; it creates hot triggers that make action immediate and effortless for motivated individuals.

A Practical Example: The Oil of Olay Story

The best example Fogg shared during his presentation was a personal one involving Oil of Olay anti-wrinkle treatments. He noticed he wasn’t consistently applying the treatment twice daily as directed—sometimes remembering in the morning but forgetting at night, or vice versa.

Recognizing he needed a reliable trigger, Fogg identified an existing habit he performed twice daily without fail: brushing his teeth. He placed the Oil of Olay treatments in the sink where he brushed his teeth, creating a physical obstacle he had to move before brushing.

This simple change transformed his adherence to the treatment regimen. By placing the product directly in his path during an established routine, he created a hot trigger at precisely the right moment—when both motivation (wanting to improve his skin) and ability (having the product at hand) were present.

This example perfectly illustrates several key principles:

- Anchor new behaviors to existing habits

- Create physical reminders that can’t be ignored

- Design for the moment of action, not just general awareness

- Make the desired behavior as simple as possible

The power of this approach is that it doesn’t rely on remembering to do something new. Instead, it leverages existing behaviors as triggers for new habits, creating a natural flow from one action to the next.

The Behavior Grid: 15 Ways Behavior Changes

Beyond the core behavior model, Fogg has developed a comprehensive framework called the Behavior Grid, which categorizes 15 different types of behavior changes based on their duration and nature.

The grid categorizes behaviors by duration:

- One time: Performing a behavior once (e.g., signing up for a newsletter)

- Fixed period: Doing a behavior for a set duration (e.g., following a 30-day diet)

- From now on: Adopting a permanent behavior change (e.g., taking medication daily forever)

Each type of behavior change requires different psychological strategies and design approaches. For instance, getting someone to click a button once (a one-time behavior) is fundamentally different from getting them to exercise regularly for the rest of their life (a “from now on” behavior).

When designing for behavior change, it’s crucial to identify exactly what type of behavior you’re targeting and tailor your approach accordingly.

Fogg’s Behavior Grid reminds us that not all behavior changes are created equal. Understanding the specific type of change you’re trying to create allows for more effective and targeted interventions.

Key Principles for Application

Based on Fogg’s presentation and his broader work, several key principles emerge for anyone looking to design for behavior change:

- Automate when possible: The best behavior changes require minimal conscious effort

- Simplify over training: Make behaviors easier rather than training harder

- Use hot triggers: Place prompts at moments when immediate action is possible

- Target motivated people: Focus on those who already want to change

- Create tiny habits: Start with behaviors so small they require minimal motivation

- Anchor to existing routines: Attach new behaviors to established habits

- Celebrate successes: Create positive emotions around behavior change

These principles can be applied across domains—from personal habit formation to product design, from health interventions to organizational change initiatives.

Successful behavior design isn’t about forcing change through willpower or manipulation. It’s about creating the conditions where desired behaviors can naturally and easily emerge.

From Theory to Practice

What makes BJ Fogg’s work so valuable is that it bridges the gap between academic behavioral science and practical application. His models provide a structured way to understand why behaviors occur (or don’t) and offer clear guidance for designing interventions that work.

Whether you’re trying to establish a new personal habit, design a product that drives user engagement, or implement organizational change, the B=MAP formula provides a powerful framework. By ensuring that motivation, ability, and prompts align at the right moment, you can dramatically increase the likelihood of successful behavior change.

Perhaps most importantly, Fogg’s approach shifts our thinking away from the traditional focus on motivation and willpower—which often fail—toward the more reliable factors of ability (simplicity) and well-designed prompts. This perspective aligns with modern understandings of habit formation and cognitive science.

As we navigate a world increasingly designed to influence our behavior—from social media platforms to health apps to workplace environments—understanding these mechanics of persuasion becomes not just useful but essential.

Join the Conversation

Have you used any of these principles to change your own behavior or to design more effective products? What hot triggers have you found most effective in your life or work? Share your experiences in the comments below!