Why the most innocent word in the English language is secretly destroying your biggest aspirations When tomorrow becomes never There's a word that appears in conversations millions of times every day. It seems harmless, even responsible. It suggests planning, consideration, and good intentions. Yet this single word has killed more dreams, destroyed more potential, and wasted more human talent than economic crashes, natural disasters, or any external obstacle you can imagine. That word is "tomorrow."...

Tag: behavioral economics

The Success Trap: Why Yesterday’s Winners Become Tomorrow’s Losers (And How to Break the Cycle)

How the very achievements that made you successful can become the greatest threat to your future success When success becomes a prison instead of a platform There's a cruel irony embedded in human achievement: the very strategies that make us successful often become the primary obstacles to our continued success. The problem with success is that it teaches you the wrong lessons. What worked yesterday becomes religion, and religions don't adapt. This isn't just philosophical...

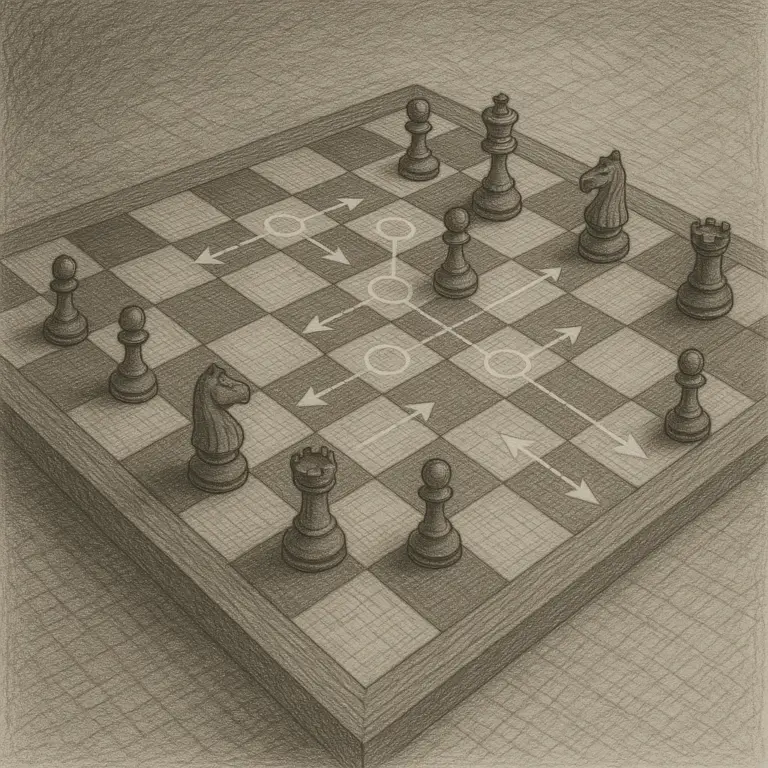

The Revolutionary Decision-Making Strategy That Amazon, Google, and Top Entrepreneurs Swear By

Why the world's most successful companies focus on making mistakes cheap rather than making them rare Strategy isn't about perfect moves—it's about quick adaptation Most people approach decision-making with a fundamental misunderstanding. They believe success comes from being right all the time—from making perfect decisions that never need correction. This mindset, while intuitive, is precisely what paralyzes individuals and organizations, preventing them from moving fast in uncertain environments. The world's most successful companies and entrepreneurs...

Book: Predictably Irrational

Kevin Rose recommended this book on this week's Diggnation which sounds interesting. You can buy it on Amazon here. Amazon's description is: "Irrational behavior is a part of human nature, but as MIT professor Ariely has discovered in 20 years of researching behavioral economics, people tend to behave irrationally in a predictable fashion. Drawing on psychology and economics, behavioral economics can show us why cautious people make poor decisions about sex when aroused. Why patients...