Sometimes the most powerful lesson comes not from getting a yes, but from someone recognizing the courage it took to ask View this post on Instagram A rejection that became the most empowering advice millions have ever heard Sophia didn't make it to the next round. In the traditional sense, her audition was a "failure." But what happened next has touched millions of people and delivered one of the most powerful life lessons ever captured...

Tag: Business Strategy

From Baseball to Billions: How Smart Leaders Turn 90% Failure Rates Into Massive Success

Master Jeff Bezos's counterintuitive approach to business strategy that transforms calculated failures into extraordinary wins Taking bold swings in business requires the courage to fail repeatedly while aiming for transformational wins Imagine being told that the key to extraordinary business success is being wrong 90% of the time. It sounds absurd, doesn't it? Yet this counterintuitive philosophy has driven some of the most successful companies and leaders of our era, from Amazon's dominance in cloud...

The Success Trap: Why Yesterday’s Winners Become Tomorrow’s Losers (And How to Break the Cycle)

How the very achievements that made you successful can become the greatest threat to your future success When success becomes a prison instead of a platform There's a cruel irony embedded in human achievement: the very strategies that make us successful often become the primary obstacles to our continued success. The problem with success is that it teaches you the wrong lessons. What worked yesterday becomes religion, and religions don't adapt. This isn't just philosophical...

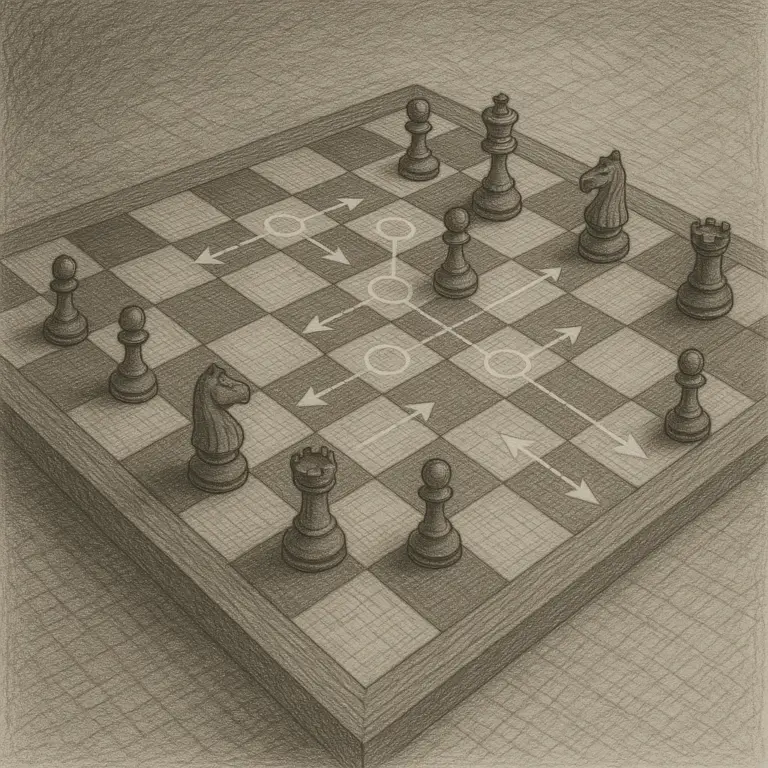

The Revolutionary Decision-Making Strategy That Amazon, Google, and Top Entrepreneurs Swear By

Why the world's most successful companies focus on making mistakes cheap rather than making them rare Strategy isn't about perfect moves—it's about quick adaptation Most people approach decision-making with a fundamental misunderstanding. They believe success comes from being right all the time—from making perfect decisions that never need correction. This mindset, while intuitive, is precisely what paralyzes individuals and organizations, preventing them from moving fast in uncertain environments. The world's most successful companies and entrepreneurs...

Survivor Strategy in Business: Outwit, Outplay, Outlast

How the strategic principles of a reality TV show mirror successful business practices The reality TV show Survivor is often described as a social experiment in strategy and human behavior. Stranded contestants must "outwit, outplay, outlast" each other for 39 days to win – a process that mirrors challenges in the business world. In both arenas, individuals navigate limited resources, intense competition, and the need to adapt under pressure. Many strategic principles that lead to...

Outrunning Money

"Honey, you have to stop chasing money because money runs really fast. You should go do the right thing. It will chase you." — Advice from Tariq Farid's mother to the Edible Arrangements CEO In this NPR interview, Tariq Farid shares the story of how he transformed a small flower shop into the global phenomenon that is Edible Arrangements. At the heart of his success lies this simple wisdom from his mother—a reminder that authentic...