How the strategic principles of a reality TV show mirror successful business practices The reality TV show Survivor is often described as a social experiment in strategy and human behavior. Stranded contestants must "outwit, outplay, outlast" each other for 39 days to win – a process that mirrors challenges in the business world. In both arenas, individuals navigate limited resources, intense competition, and the need to adapt under pressure. Many strategic principles that lead to...

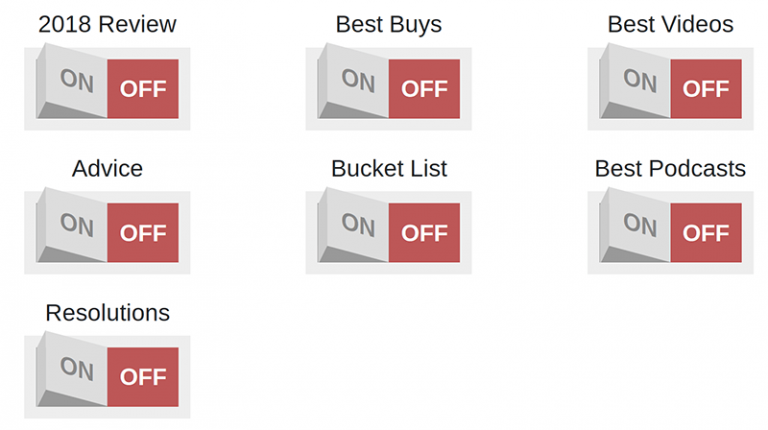

Reflecting on 2018 & Charting New Paths for 2019

I'm thrilled to unveil my brand new interactive experience: My 2019 Resolutions & 2018 Year in Review. This project became much more than just a simple tracker—it evolved into a meaningful journey of reflection, celebration, and intentional goal-setting for the upcoming year. Click on the image to explore the interactive experience Join the Conversation What reflection tools do you use to look back on your year? How do you set meaningful goals for the future?

A Brief Encounter: My Memory of Anthony Bourdain

Always moving forward, yet seeking solitude in a crowded world. Unfiltered Honesty with Unwavering Compassion I respected Bourdain because very few people in life have the ability to courageously speak their mind while remaining open-minded. Society is enamored with the unfiltered "what will they say next" personality until they say something over the line. Bourdain seemed to always understand that line and gave us just the right dose of reality when unpacking lessons learned during...

Mid-Year Check-In: My 2018 Resolutions Journey

We are half way through 2018 and I realized I neglected to share my resolutions with you here on my blog. These are some of my favorite "personal time" creative projects I work on each year. Hope you enjoy it as much as I did creating it!

The Best Ideas Die in the Shower

On this episode of 'Masters of Scale,' Linda Rottenberg talks about how the best ideas originate in the shower, but too often they never escape the bathroom.

Chris Hadfield’s Advice for When Kids Say “Can’t”