🤖

AI-Assisted Research This article was created with AI assistance

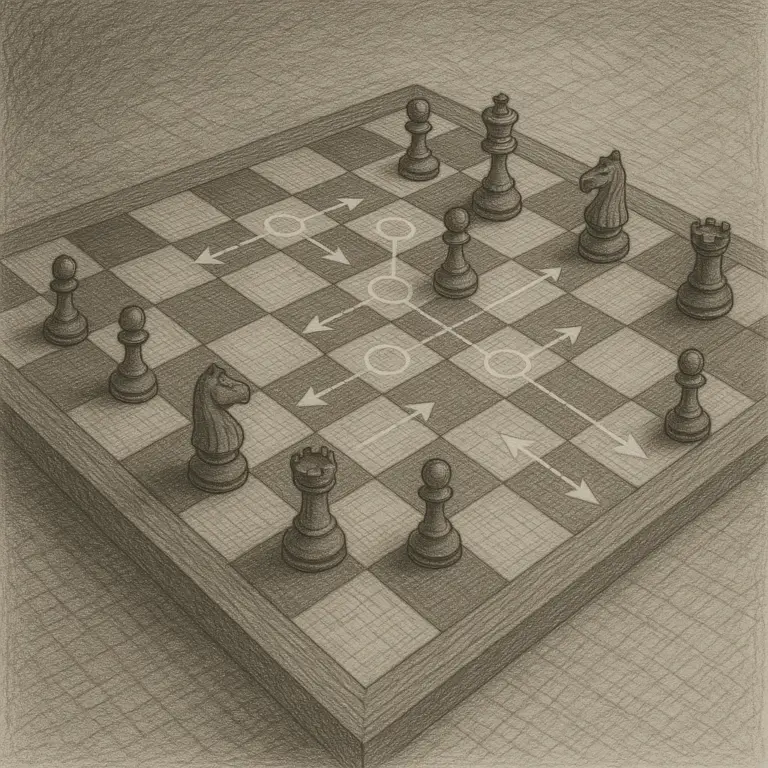

Why the world's most successful companies focus on making mistakes cheap rather than making them rare Strategy isn't about perfect moves—it's about quick adaptation Most people approach decision-making with a fundamental misunderstanding. They believe success comes from being right all the time—from making perfect decisions that never need correction. This mindset, while intuitive, is precisely what paralyzes individuals and organizations, preventing them from moving fast in uncertain environments. The world's most successful companies and entrepreneurs...