Why the most innocent word in the English language is secretly destroying your biggest aspirations When tomorrow becomes never There's a word that appears in conversations millions of times every day. It seems harmless, even responsible. It suggests planning, consideration, and good intentions. Yet this single word has killed more dreams, destroyed more potential, and wasted more human talent than economic crashes, natural disasters, or any external obstacle you can imagine. That word is "tomorrow."...

The Success Trap: Why Yesterday’s Winners Become Tomorrow’s Losers (And How to Break the Cycle)

How the very achievements that made you successful can become the greatest threat to your future success When success becomes a prison instead of a platform There's a cruel irony embedded in human achievement: the very strategies that make us successful often become the primary obstacles to our continued success. The problem with success is that it teaches you the wrong lessons. What worked yesterday becomes religion, and religions don't adapt. This isn't just philosophical...

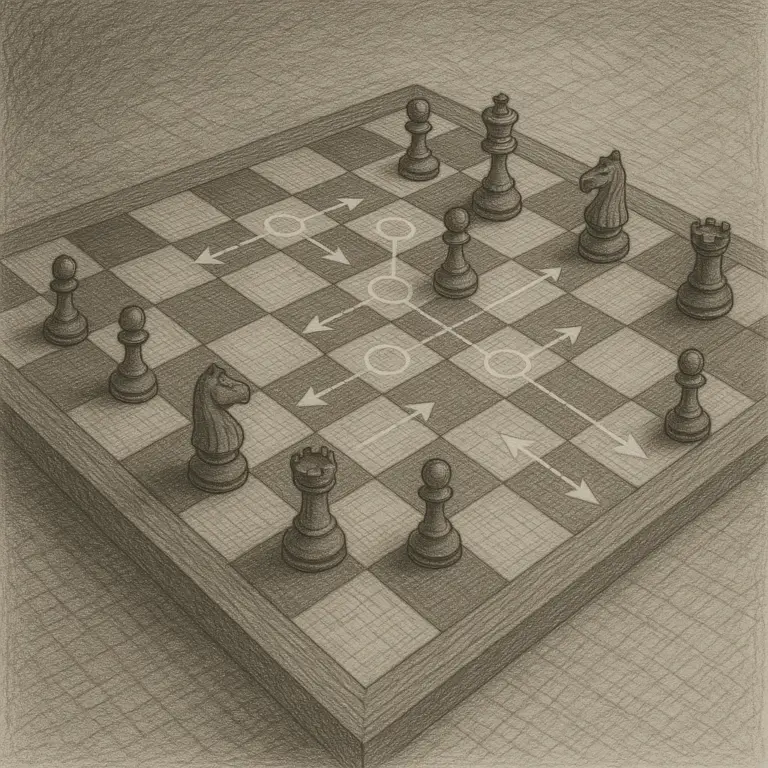

The Revolutionary Decision-Making Strategy That Amazon, Google, and Top Entrepreneurs Swear By

Why the world's most successful companies focus on making mistakes cheap rather than making them rare Strategy isn't about perfect moves—it's about quick adaptation Most people approach decision-making with a fundamental misunderstanding. They believe success comes from being right all the time—from making perfect decisions that never need correction. This mindset, while intuitive, is precisely what paralyzes individuals and organizations, preventing them from moving fast in uncertain environments. The world's most successful companies and entrepreneurs...

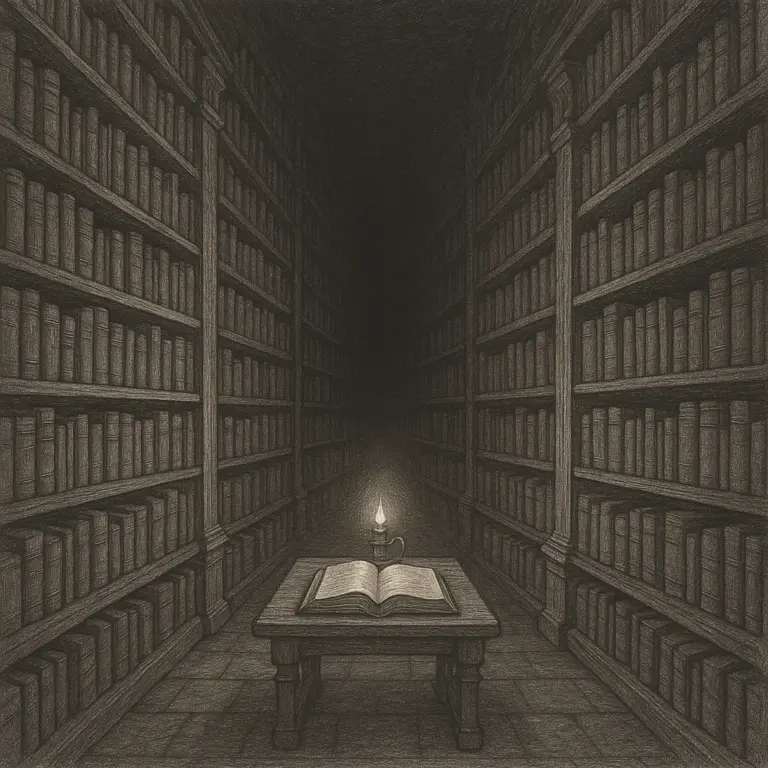

Why Collecting Information Isn’t Learning: Schopenhauer’s Timeless Warning About Knowledge vs. Wisdom

How a 19th-century philosopher predicted our modern struggle with information overload and revealed the secret to true learning The difference between collecting books and gaining wisdom In our age of endless scrolling, bookmarked articles, and information overwhelm, a 19th-century German philosopher offers a warning that feels startlingly modern. Arthur Schopenhauer, writing long before the internet existed, identified a fundamental problem with how we approach learning: the dangerous illusion that accumulating information equals gaining knowledge. "You...

5,000 Years of History Reveal Why Our Civilization Is Destined for Self-Destruction

Cambridge researcher's groundbreaking analysis of human societies reveals the hidden patterns driving us toward global collapse—and the radical changes needed to survive The ruins of past empires tell a story we're still refusing to hear What if everything we've been told about human progress is fundamentally wrong? What if "civilization" itself is nothing more than sophisticated propaganda designed to justify domination? These aren't the musings of a fringe theorist—they're the conclusions of Dr. Luke Kemp,...

Fact-Checking David Sacks’ “1,000,000× in Four Years” AI Progress Claim

Analyzing the exponential acceleration in AI capabilities through advances in models, chips, and compute infrastructure The three vectors of AI advancement: algorithms, hardware, and compute scaling Venture capitalist David Sacks recently argued that artificial intelligence is on track for a million-fold (1,000,000×) improvement in four years, driven by exponential advances in three areas: models/algorithms, chips, and compute infrastructure. In a podcast discussion, Sacks stated that AI models are getting "3–4× better" every year, new hardware...